Waters of the United States: A Continuing Controversy

By EnviroScience Senior Ecologist Michael Liptak, Ph.D.

The 1972 Water Pollution Control Act, also known as the Clean Water Act, directed the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) to protect the integrity of our Nation’s waters by establishing a permit process to regulate activities that would affect water quality.

Under the Clean Water Act, the USACE regulates the placement of fill into the Waters of the U.S. However, the Clean Water Act did not define the phrase “Waters of the U.S.,” now commonly abbreviated as WOTUS. The regulated public was left with uncertainty about how far upstream from navigable water federal authority extends. Does it include tributaries? What about ephemeral streams? What about wetlands, ponds, and lakes?

The USACE and the USEPA developed regulatory guidance to interpret these requirements and relieve some of this uncertainty, with varying degrees of success. In addition, the reach of federal authority over aquatic systems has been interpreted in several U.S. Supreme Court decisions.

The USACE and the USEPA developed regulatory guidance to interpret these requirements and relieve some of this uncertainty, with varying degrees of success. In addition, the reach of federal authority over aquatic systems has been interpreted in several U.S. Supreme Court decisions.

In Riverside Bayview v. USACE (1985), the Court ruled unanimously in favor of the USACE, establishing that wetlands adjacent to jurisdictional streams can be regulated under the Clean Water Act. In Solid Waste Agency of Northern Cook County v. USACE (2001), the Court ruled against the USACE, stating that the presence of migratory birds alone was insufficient to claim federal authority over isolated wetlands.

Wetlands must have a significant nexus with downstream waters in order to be regulated under the Clean Water Act. The Court revisited this issue again in 2006 with the cases John A. Rapanos, et ux., et al., Petitioners v. United States; June Carabell, et al., Petitioners v. United States Army Corps of Engineers, et al., commonly called the Rapanos decision. This resulted in a split decision (4-1-4) with five opinions issued: Scalia, with Roberts and Kennedy concurring, and Breyer and Stevens with separate dissents.

Under the Scalia ruling, wetlands and streams had to be relatively permanent waters connected with downstream aquatic resources. In Kennedy’s concurring opinion, he offered a different test: if a water could be shown to significantly affect the water quality of downstream aquatic resources under federal jurisdiction (i.e., if it had a “significant nexus”), that stream or wetland was under federal jurisdiction—even if it was not relatively permanent water. The USACE and the USEPA adopted both tests and released guidance accordingly.

Under the Scalia ruling, wetlands and streams had to be relatively permanent waters connected with downstream aquatic resources. In Kennedy’s concurring opinion, he offered a different test: if a water could be shown to significantly affect the water quality of downstream aquatic resources under federal jurisdiction (i.e., if it had a “significant nexus”), that stream or wetland was under federal jurisdiction—even if it was not relatively permanent water. The USACE and the USEPA adopted both tests and released guidance accordingly.

In 2015, the Obama Administration issued a rule known as the Clean Water Rule or the 2015 WOTUS Rule. It contained bright line, distance-based boundaries within which all wetlands and streams were jurisdictional and allowed for regulation of isolated wetlands if they affected downstream water quality in association with other similarly situated wetlands. This was controversial, and several lawsuits resulted in a patchwork of enforcement across the country.

The Trump Administration rescinded the Clean Water Rule and adopted the Navigable Waters Protection Rule (NWPR), which became effective June 22, 2020. The NWPR had a narrower interpretation of federal authority that disregarded the Kennedy “significant nexus test” and only considered the Scalia “relatively permanent water test” to be applicable. Subjected to lawsuits, the NWPR was eventually vacated in 2021. At that point, the definition of what constitutes “Waters of the U.S.” reverted to the post-Rapanos guidance issued by the agencies.

The Biden Administration is the latest to attempt to create a durable WOTUS definition. On January 18, 2023, the final “Revised Definition of ‘Waters of the United States'” rule was published in the Federal Register, and the “2023 WOTUS Rule” took effect on March 20, 2023. The WOTUS Rule reaffirms the use of both the relatively permanent water standard endorsed by Scalia and the significant nexus standard endorsed by Kennedy—effectively returning the nation to the regulations that were in effect since 2006 and the guidance which was originally released in 2008.

Much like the previous two attempts to define federal jurisdiction, the 2023 WOTUS Rule immediately led to lawsuits by a number of businesses, organizations, and state attorneys general. On March 19, 2023, U.S. District Judge Jeffrey Vincent Brown issued a preliminary injunction staying the implementation of the 2023 WOTUS Rule in Texas and Idaho. His ruling separately rejected a request to block enforcement nationwide.

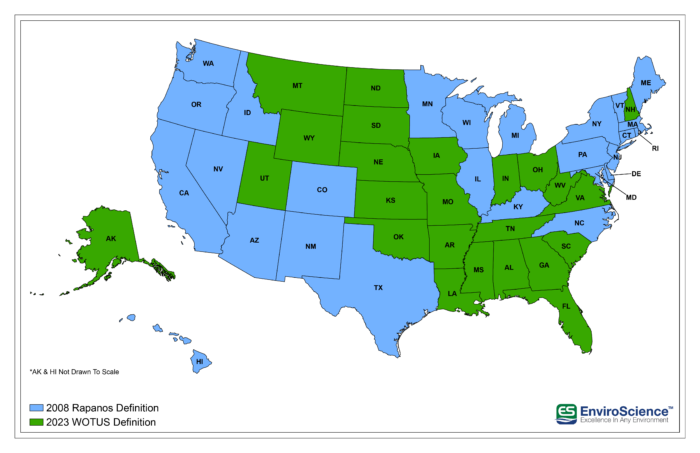

On April 12, 2023, U.S. District Judge Daniel L. Hovland issued another preliminary injunction staying the implementation of the 2023 WOTUS Rule in 24 additional states. “Suffice it to say the Clean Water Act and the varied and different definitions of ‘Waters of the United States’ have created nothing but confusion, uncertainty, unpredictability, and endless litigation throughout this country to date,” wrote Hovland in his injunction. These 24 states include Alabama, Alaska, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Iowa, Indiana, Kansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, New Hampshire, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Utah, Virginia, West Virginia, and Wyoming. As a result of these two injunctions, the USEPA and the USACE are interpreting “Waters of the United States” as consistent with the pre-2015 regulatory regime in these 26 states until further notice.

It is important to note that since 1972, ongoing agricultural, silvicultural, and ranching activities are exempt from the provisions of the Clean Water Act under the provisions of Section 404 (f). Exempt activities include farming, silviculture, and ranching activities; emergency maintenance activities; construction and maintenance of farm ponds, stock ponds, or irrigation ditches or the maintenance of drainage ditches; construction of temporary sedimentation basins; any activity with respect to which a State has an approved program under section 208(b)(4) of the CWA (not currently available in New Mexico); and construction or maintenance of farm roads, forest roads, or temporary roads for moving mining equipment.

It is important to note that since 1972, ongoing agricultural, silvicultural, and ranching activities are exempt from the provisions of the Clean Water Act under the provisions of Section 404 (f). Exempt activities include farming, silviculture, and ranching activities; emergency maintenance activities; construction and maintenance of farm ponds, stock ponds, or irrigation ditches or the maintenance of drainage ditches; construction of temporary sedimentation basins; any activity with respect to which a State has an approved program under section 208(b)(4) of the CWA (not currently available in New Mexico); and construction or maintenance of farm roads, forest roads, or temporary roads for moving mining equipment.

A lawsuit (Sackett v. EPA) currently before the U.S. Supreme Court could also affect the reach of federal authority over wetlands. The case was argued in October 2022 and a decision is expected in June 2023. Whether it will add clarity to the issue or further muddy the waters remains to be seen. In summary, the recent lawsuits have led to 26 states operating under the 2008 Rapanos guidance, while 24 states will operate under the definition of Waters of the United States from 2023. The upcoming SCOTUS ruling on the Sackett case may (or may not) provide additional clarity on this divisive issue.

Few environmental firms in the country retain EnviroScience’s degree of scientific know-how, talent, and capability under one roof. The diverse backgrounds of our biologists, environmental engineers, scientists, and divers enable us to provide comprehensive in-house services and an integrated approach to solving environmental challenges—saving clients time, reducing costs, and ensuring high-quality results.

Our client guarantee is to provide “Excellence in Any Environment,” meaning no matter what we do, we will deliver on our Core Values of respect, client advocacy, quality work, accountability, teamwork, and safety. EnviroScience was created with the concept that we could solve complex problems by empowering great people. This concept still holds true today as our scientists explore the latest environmental legislation and regulations and incorporate the most up-to-date technology to gather and report data.

EnviroScience expertise includes but is not limited to aquatic surveys (including macroinvertebrate surveys and biological assessments); ecological restoration; ecological services (including impact assessments, invasive species control, and water quality monitoring); emergency response; engineering and compliance services; endangered mussel surveys; laboratory and analysis; stormwater management; threatened and endangered species; and wetlands and streams (including delineation and mitigation). Further, EnviroScience is one of the few biological firms in the country that is a general member of the Association of Diving Contractors International (ADCI) and offers full-service commercial diving services.